A friend was going through case studies at a venture firm and one of the questions asked how he would think about financing / funding. The case study attached an equity cap table. Although I’ve seen cap tables previously, they’ve primarily been for liens of debt. This is a different ball game. It’s not about who gets paid what first or when something is due, it’s about ownership, and if you’re an investor, your MoM multiples(Money on Money). I’ll explain more below.

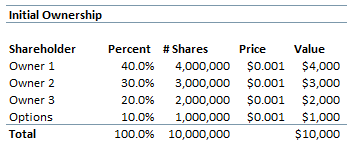

Generally, a fund will want to raise seed funding upon the inception of a good idea / team. This comes after incorporating the company, determining the shares, split, and ownership, among other operational tasks. For the purposes of the example I’ll lay out below, let’s just assume there are 10mm shares, at par value of $0.001 created.

The cap table would look like

This is relatively simple. By the court of law, the Delaware C Corp is worth $10,000, and has $10mm shares outstanding divided among three owners and an existing options pool for future employees. We’re all set for seed funding.

Note that there are two types of seed rounds: priced and unpriced.

- Priced seed round: Company is given a valuation, nothing new here, similar to Series A fundraising. Shares in the company are purchased by investors at a price determined by that valuation (i.e. $3mm seed round valuation, 10mm shares outstanding price per share = $0.30/share)

- Unpriced seed round: No valuation, and investor isn’t purchasing known amount of equity. More like an agreement between investor and company to issue shares at later priced round for cash

Especially in the unpriced seed rounds, investors want to protect their downside, so there are certain provisions that Seed investors impose on these funding terms. Two common provisions are (1) discount provision (2) valuation cap. These seed investors deploy their capital using two main funding “instruments”, (1) a Simple Agreement for Future Equity (“SAFE”) note, or (2) a Convertible note, which is a lot like debt except that it converts to equity under predetermined conditions such as raising a priced round.

The main difference between a SAFE note and a convertible note is that SAFE notes are generally, as the name implies, safer for the entrepreneur. Unlike convertible notes, they have no interest or maturity dates. This was actually founded in 2013 by Y Combinator and is generally agreed to be better for founders.

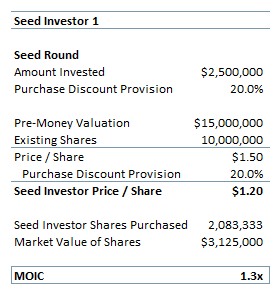

So what do these provisions look like on seed investors’ returns? Well, let’s assume the company is burning through its cash and needs to finance a new round, a Series A. In this round, investors determine the value of the company to be $15mm. With 10mm outstanding shares, that prices each share at $1.50.

In the event the seed investor (“Seed 1”) invested $2.5mm in a SAFE with the ability to purchase shares at a 20% discount to the pre-money valuation, Seed 1 can purchase each share at $1.20. The $2.5mm translates now to ~2mm shares, valued at $3.1mm, or a 1.25x money on money on money multiple. It’s easier to visualize this below:

A valuation cap does roughly the same thing. Say seed investor 2 (“Seed 2”) invests $2.5mm in a SAFE with a valuation cap of $10mm, allowing them to buy shares resulting in 2.5mm shares from the seed investment because each share is essentially worth $1 to them. At the new share price of $1.50/share, the investor scores a 1.5x MoM multiple. It’s essentially a 50% discount to pre-money valuation. Two sides of a coin basically. Visualization below:

Pretty easy stuff, and also pretty modest valuation expectations. On an intuitive level, it might make more sense for investors to use the valuation cap method, because the upside could be tremendous, even if it is at the cost of ownership dilution, to capture the upside of a startup raising a significant amount in their Series A. For instance, if the valuation cap is at $10, and the pre-money valuation is $30mm, that’s a 3.0x MoM!

Cool cool, so seed investors, done. Moving on to the big check writers, or, well, relatively bigger – the Series A folks.

Companies generally raise Series A when they’re valued at $15mm – $30mm, and the average funding amount is approximately $10.5mm. VCs who invest in this round include folks at Sequoia, Bessemer, GV, Accel, among others. If a company gets to raise Series A, it usually means there is a product-market-fit / growth strategy moving forward buuuut hey, even startups that raise hundreds of millions can fail (link).

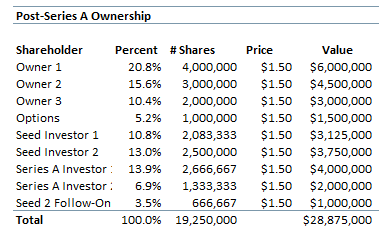

In this round, the founders realize they need around $7mm in capital. Three investors bite, two of which are new investors, and the last is a follow-on investment from Seed 2.

Now, the company has issued around 4.7mm new shares on top of the 10mm they initially started with. Let’s look at what that does to the ownership dilution.

A better visualization:

Basically, post seed and series A, the company has given away nearly half of its ownership and is now valued at ~$30mm. Not a bad gig!

The logic flows to other series as well, and as you can imagine, existing shareholders get further diluted as the company raises more capital. Feel free to tinker around with my excel attached: Cap Table